By: Talib Williams

I was at breakfast this morning with a friend of mine, having our normal morning political conversations, when this friend began talking about Obama’s recent act of benevolence. According to an article by NPR:

“President Obama granted clemency to more than 200 people yesterday. Among them was Oscar Lopez Rivera. He has been in prison since 1981. To his supporters, he is a freedom fighter for the cause of Puerto Rican Independence. To others, he is a terrorist.”

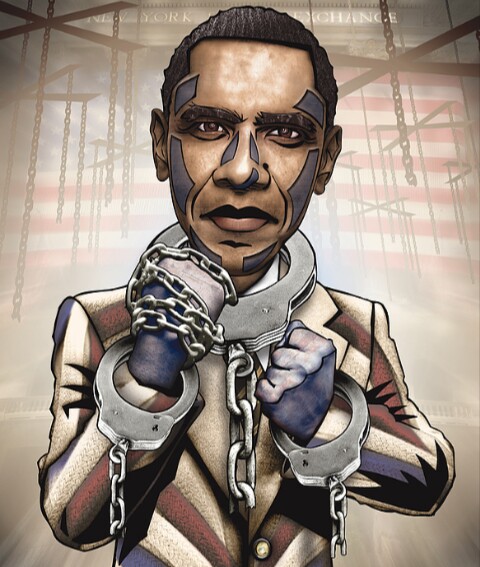

These 200 people included political prisoners of all ethnicities. Except for African Americans. We were glad to see a political prisoner released after serving so long. We were equally as enthused that it was at the suggestion of Hamilton star, Lyn Manuel Miranda, that this prisoner was released. But why hadn’t the first black president released a single African American political prisoner? My friend sounded hurt. This hurt was immediately glossed over by a resigned look of understanding, and his closing statement that: “a slave doesn’t rebel.”

Obama’s White House career, from campaign to presidency, revealed that he wasn’t willing to go out on a limb for those who seemed to find the most hope in what his presidency could mean. And for that, he was referred to by many who felt that he could have taken a stronger stance, as nothing more than a field hand.

When Obama began to run for office, our communities were excited about what an Obama leadership could change. Chief among the things an Obama presidency could mean for African Americans, was at least the possibility of reopening the conversation of the ever elusive reparations. (See Ta-Nehisi Coates’ “The Case For Reparations”) That was until Obama made it clear that this, for him, was off the table.

He said:

To black people, the statement was clear. What we heard was “look you guys, it was already hard enough to make it this far. To speak on reparations (or anything solely concerning black people) would spell a certain defeat. I can’t afford to place this presidency in jeopardy by supporting such causes.” However, we still had hope. We believed that once in office, his position would change. It never did.

Then, when he won his second term, and it was coming to an end, we believed that he, having nothing to loose, would be bold enough to do what he hadn’t done the entire two terms of his presidency. At the very least, he would make a public apology for America’s involvement in slavery. Something not one American president has ever done. But he didn’t.

So when he began to pardon political prisoners throughout federal institutions across America, and failed to include the very African Americans who brought political prisoners to the world’s attention, this only solidified his role as a field hand. His concern seemed to be nothing other than upholding the status quo. He wouldn’t even grant a posthumous pardon to the late Marcus Garvey. An open letter was written to Obama before he left office, asking that he pardon:

Assata Shakur, Jamil Abdullah Al-Amin (Rap Brown), Dr. Mutulu Shakur, Fred “Muhammad” Burton, Patrice Lumumba Ford, Mumia Abu-Jamal, Agona Azania, Veronza Bowers Jr., Romaine “Chip” Fitzgerald, Joseph “Joe-Joe” Bowen, Jeff Fort (Chief Malik), Robert Seth Hayes, Kamau Sadiki (Freddie Hilton), Larry Hoover, Richard Mafundi Lake, Maliki Shakur Latine, Ruchell Cinque Magee, Reverend Joy Powell, Ronald Reed, Kojo Bomani Sababu, Russell Maroon Shoatz, Sundiata Acoli (C. Squire), Kenny Zulu Whitmore, Chuck Sims Africa, Debbie Sims Africa, Delbert Orr Africa, Edward Goodman Africa, Janet Holloway Africa, Janine Phillips Africa, Michael Davis Africa, Herman Bell, Jalil Muntaqim, Leonard Peltier, Abdul Azeez (Warren Ballentine), Hanif Shabazz Bey (Beaumont Gereau), Malik Smith (Meral Smith), Marcus Garvey.

This request was denied. Then again, what else were we to expect? Slaves don’t rebel.